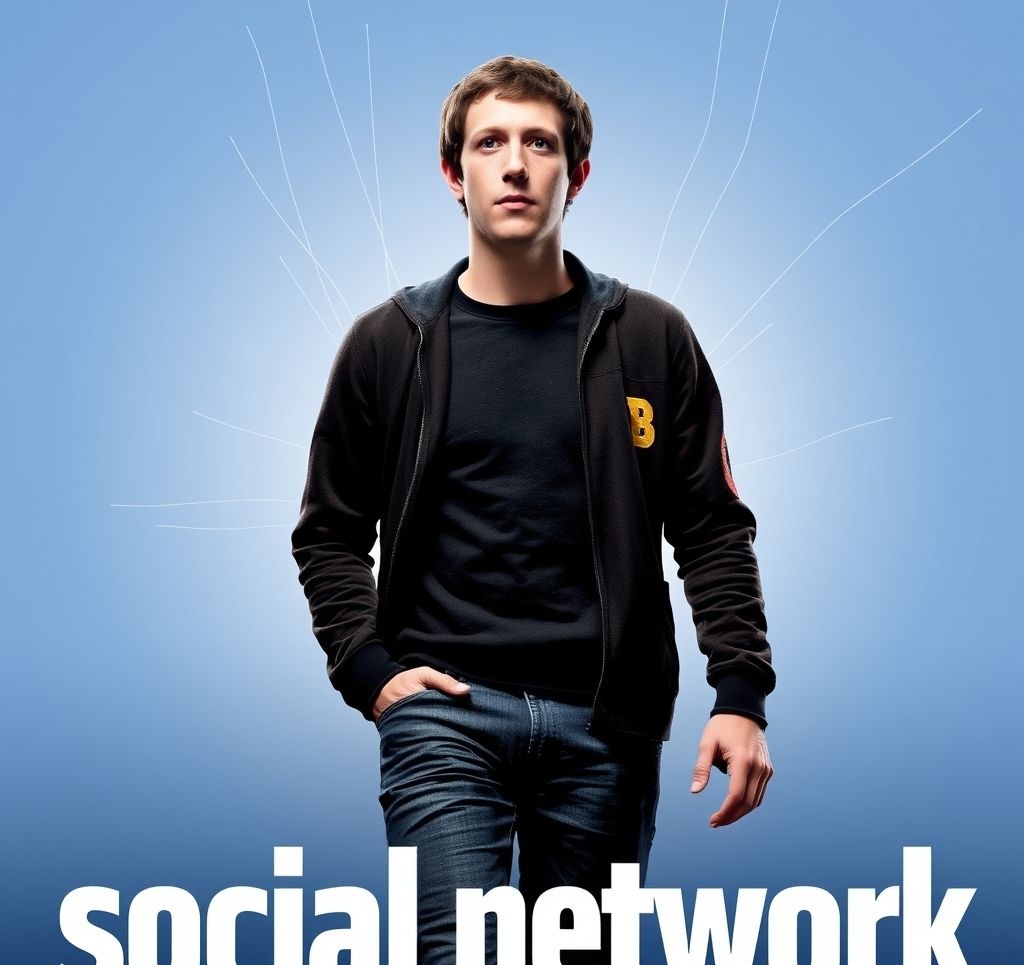

The Social Network (2010)

Movie Details

- Release Date: October 1, 2010

- Director: David Fincher

- Screenplay: Aaron Sorkin (based on the book "The Accidental Billionaires" by Ben Mezrich)

- Cinematography: Jeff Cronenweth

- Music: Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross

- Budget: $40 million

- Box Office: $224.9 million

- Production Companies: Columbia Pictures, Relativity Media, Scott Rudin Productions, Trigger Street Productions

Cast

- Jesse Eisenberg as Mark Zuckerberg

- Andrew Garfield as Eduardo Saverin

- Justin Timberlake as Sean Parker

- Armie Hammer as Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss

- Max Minghella as Divya Narendra

- Rooney Mara as Erica Albright

- Brenda Song as Christy Lee

- Rashida Jones as Marylin Delpy

- John Getz as Sy

- David Selby as Gage

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Awards: Won 3 Oscars (Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Original Score, Best Film Editing)

- Academy Awards: Nominated for 5 additional Oscars including Best Picture and Best Director

- Golden Globe Awards: Won 4 (Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Original Score)

- BAFTA Awards: Won 3 (Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Editing)

- National Board of Review: Best Film, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor (Jesse Eisenberg)

- AFI Awards: Movie of the Year

Synopsis & Analysis

Synopsis

In 2003, Harvard student Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) is dumped by his girlfriend Erica Albright (Rooney Mara). Returning to his dorm, the embittered Mark creates a website called Facemash that allows users to rate female Harvard students' attractiveness using stolen photos from university databases. The site generates so much traffic it crashes Harvard's network.

This incident brings Mark to the attention of twins Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss (both played by Armie Hammer) and their business partner Divya Narendra (Max Minghella), who recruit him to code their social networking site, Harvard Connection. Instead, Mark develops his own site, "TheFacebook," with financial support from his friend and classmate Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield).

As TheFacebook grows in popularity, it attracts the attention of Napster co-founder Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake), who becomes an advisor and helps secure venture capital. Meanwhile, the Winklevoss twins and Narendra sue Mark for intellectual property theft, and Eduardo finds himself increasingly marginalized in the company he helped create. The film is framed through two parallel depositions from lawsuits against Zuckerberg: one from the Winklevoss twins and Narendra, and another from Eduardo.

Thematic Analysis

The Cost of Ambition

At its core, "The Social Network" is a meditation on ambition and its price. Mark Zuckerberg's relentless drive to create "the next big thing" comes at a devastating personal cost—alienating friends, colleagues, and romantic interests. The film portrays success and connection as inversely related: as Facebook connects millions of users, its creator becomes increasingly isolated. The parallel lawsuits frame the narrative as the aftermath of ambition, showing how Mark's single-minded pursuit of success fractured his personal relationships.

Power and Betrayal in the Digital Age

The film explores how power dynamics shift in the emerging landscape of tech entrepreneurship. Traditional power centers (represented by the privileged Winklevoss twins) are disrupted by the meritocratic but ruthless new tech elite. Eduardo's betrayal represents the film's most poignant exploration of how power corrupts relationships. The infamous "dilution" scene—where Eduardo discovers his ownership stake has been reduced from 34% to 0.03%—serves as the emotional climax of the friendship's dissolution, highlighting how capital and control become the ultimate arbiters of power in the tech world.

Creation Myths and Authorship

The film questions the nature of creation and ownership in the digital age. Did Mark steal the Winklevosses' idea or merely improve upon a concept already in circulation? The film deliberately presents multiple, contradictory accounts of Facebook's origins, suggesting that in the collaborative world of technology, authorship is ambiguous. As lawyer Sy (John Getz) tellingly states, "Creation myths need a devil"—suggesting that the narrative of Facebook's founding necessitates both heroes and villains, regardless of the messy reality.

Class and Social Hierarchy

The film contrasts old and new forms of social capital. The Winklevoss twins represent traditional privilege—wealthy, connected, members of exclusive Harvard clubs—while Zuckerberg represents a meritocratic but resentful outsider seeking to disrupt established hierarchies. Facebook itself embodies this tension: born from Zuckerberg's exclusion from elite social circles, it ultimately creates a new form of social hierarchy based on likes, connections, and digital presence rather than inherited privilege. The Phoenix Club scene, where Mark watches the Winklevosses through a window, visually encapsulates his status as both observer and disruptor of these social hierarchies.

The Irony of Social Connection

Perhaps the film's most biting insight is the irony that Facebook—a platform designed to facilitate human connection—was created by someone portrayed as fundamentally disconnected from normal human interaction. The final scene, where Mark repeatedly refreshes his friend request to Erica, perfectly encapsulates this irony: the architect of the world's largest social network reduced to seeking validation through the very system he created. This circular narrative suggests that despite revolutionizing how billions connect online, Mark remains trapped in the same social longing that motivated him at the film's beginning.

Key Scenes Analysis

The Opening Breakup

The film opens with a virtuosic five-minute dialogue scene between Mark and Erica that establishes the film's rapid-fire verbal style and Mark's character. The scene is shot mostly in tight close-ups, emphasizing the intimacy being destroyed, and employs Aaron Sorkin's characteristic overlapping dialogue to create a sense of Mark's racing mind. The scene ends with Erica's devastating line, "You're going to go through life thinking that girls don't like you because you're a nerd. And I want you to know, from the bottom of my heart, that that won't be true. It'll be because you're an asshole." This establishes the film's core emotional wound—Mark's social rejection—that motivates the creation of Facebook.

The Facemash Creation Sequence

Following the breakup, Mark retreats to his dorm room and creates Facemash in a haze of wounded ego and alcohol. Fincher intercuts between Mark coding and a party at a final club, creating a visual contrast between isolation and social connection. This sequence employs rapid editing, voice-over blogging, and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross's pulsing score to convey both the thrill of creation and the toxic misogyny underlying the project. The sequence culminates with the site's viral spread across campus, establishing the pattern of technological innovation born from social resentment that will define the film.

The "Million Dollar" Deposition Scene

When Cameron Winklevoss suggests settling their lawsuit for a "mere" million dollars, Mark responds, "A million dollars isn't cool. You know what's cool? A billion dollars." This line, actually delivered by Sean Parker in an earlier scene and deliberately misattributed during the deposition testimony, serves as the thematic hinge of the film. It captures the scale of ambition that drives Mark and the emerging tech industry, while also revealing how narratives become distorted in retrospect. The scene's framing in the sterile deposition room, with lawyers mediating all interaction, emphasizes how direct human connection has been replaced by legal and financial calculation.

Eduardo's Confrontation with Mark

After discovering his shares have been diluted, Eduardo confronts Mark at the Facebook office in a scene of controlled fury. Andrew Garfield's performance transitions from shock to rage as Eduardo says, "I was your only friend. You had one friend." The scene is shot to emphasize Eduardo's isolation—he stands alone against Mark, Sean, and the lawyers. The destruction of a laptop serves as a physical manifestation of the friendship's violent rupture. This scene functions as the emotional climax of the film, revealing the personal cost of Facebook's success.

The Final Scene

The film ends with Mark, now the youngest billionaire in the world, alone in a conference room repeatedly refreshing his friend request to Erica Albright. The camera slowly pushes in on his face as Trent Reznor's plaintive piano piece "Hand Covers Bruise" plays. This quiet, contemplative ending stands in stark contrast to the verbal dexterity of the rest of the film. Mark's silence speaks volumes about his emotional state, suggesting that despite his unprecedented success, he remains defined by the rejection that opened the film. This circular structure implies that for all of Facebook's growth, its creator remains emotionally static, still seeking the validation that inspired the platform's creation.

Visual Style & Technical Analysis

Fincher's Visual Approach

David Fincher's precise, controlled visual style perfectly complements the film's exploration of cold ambition and technological disruption. Working with cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, Fincher employs a muted color palette dominated by yellows, ambers, and blacks that gives the film a distinctive look that's both contemporary and slightly sickly. Harvard is portrayed in warm amber tones contrasted with the cool blues of the winter exteriors, while the California scenes adopt a brighter but equally artificial tech-startup palette.

Fincher, known for his perfectionism, often required dozens of takes for seemingly simple scenes, resulting in performances of remarkable precision. The film's visual language employs exacting compositions with deliberate camera movements that reflect the emotional and power dynamics between characters. Scenes of coding and technological creation are rendered visually dynamic through creative editing and lighting, turning the potentially static activity of typing into something kinetic and engaging.

Sorkin's Screenplay and Dialogue

Aaron Sorkin's screenplay provides the film's architectural backbone, employing his signature rapid-fire, hyper-articulate dialogue to create characters who use language as both weapon and shield. The screenplay's structure—framing the narrative through two parallel depositions—allows for multiple, contradictory perspectives on the same events, highlighting the film's theme of contested narratives. Sorkin's approach creates a heightened realism where characters don't speak as people actually talk but rather as they might wish to talk if given endless opportunities to craft the perfect retort.

The screenplay's brilliance lies in its ability to make corporate machinations and coding sequences dramatically compelling through language that crackles with wit, resentment, and ambition. Key lines—such as Eduardo's "I was your only friend" or Sean Parker's entrance declaring "Sean Parker. Founded Napster when he was 19. Changed the music industry forever"—function as both character development and thematic punctuation, revealing personalities through carefully crafted self-presentation.

Sound Design and Score

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross's innovative, Oscar-winning score combines electronic elements with traditional instrumentation to create a soundscape that feels both contemporary and timeless. Their reimagining of Grieg's "In the Hall of the Mountain King" for the Henley Royal Regatta sequence demonstrates how the score adapts classical elements for a digital age, mirroring the film's thematic concerns. The score often creates tension between what's seen and what's heard, with seemingly triumphant moments undercut by dissonant, unsettling musical cues.

The sound design employs subtle environmental details to establish setting—the echoing emptiness of Harvard hallways, the chaotic energy of parties, the sterile quiet of deposition rooms. Dialogue is often layered over these environments in ways that enhance the film's themes, with conversations frequently occurring in spaces where characters struggle to hear or understand each other, reinforcing the film's exploration of miscommunication and perspective.

Editing and Narrative Structure

Editors Kirk Baxter and Angus Wall (who won an Academy Award for their work) create a complex temporal structure that moves fluidly between the lawsuits and the events that precipitated them. Rather than feeling disorientating, these transitions create thematic resonances between past actions and present consequences. The editing employs both classical techniques—such as match cuts that connect related ideas across time and space—and more contemporary approaches including rapid montages that compress time during the creation sequences.

The film's pacing is remarkable for its ability to maintain momentum despite being primarily composed of people talking in rooms. The editors create a propulsive rhythm through precise cutting that often operates in counterpoint to the actors' performances, cutting away from reactions just before they're complete or lingering slightly longer than comfortable to create subtle emotional effects. This technical precision mirrors the film's portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg himself—brilliant, exacting, but somehow missing crucial human elements.

Cultural Context & Impact

Relationship to Reality

Upon its release, much was made of "The Social Network's" relationship to factual events. Mark Zuckerberg himself criticized the film's accuracy, particularly its portrayal of his motivations as stemming from social rejection rather than creative interest. The film takes significant dramatic license with real events—the character of Erica Albright, for instance, is largely fictional, and many timelines are compressed for dramatic effect.

However, Fincher and Sorkin were explicit that they were creating a dramatization rather than a documentary. Sorkin famously stated, "I don't want my fidelity to be to the truth; I want it to be to storytelling." The film thus functions less as a factual account of Facebook's founding and more as a Shakespearean exploration of power, betrayal, and ambition set against the backdrop of the early 21st century tech revolution. Its portrayal of Zuckerberg as brilliant but wounded, ambitious but lonely, has nonetheless significantly shaped public perception of the real-life figure.

Capturing the Tech Zeitgeist

Released in 2010, the film arrived at a pivotal moment in the evolution of social media and tech culture. Facebook had grown from a college networking site to a global platform with over 500 million users, but before many of the controversies that would later engulf the company. The film presciently captures the transition of tech from dorm-room hobby to world-changing industry, portraying the moment when the ethos of "move fast and break things" began to reshape global communication.

The film's exploration of how technology mediates social relationships now appears prophetic, as does its questioning of the ethics of data ownership and privacy. Sean Parker's line, "We lived on farms, then we lived in cities, and now we're going to live on the internet," has proven remarkably accurate as a prediction of social media's centrality to contemporary life. Similarly, the film's portrayal of the tension between connection and isolation in digital spaces anticipated much of the subsequent discourse around social media's psychological effects.

The Film's Legacy

"The Social Network" is now widely regarded as one of the defining films of its decade, both for its artistic merits and its cultural insights. It has influenced subsequent biopics and tech dramas, establishing a template for making the seemingly mundane world of coding and business meetings visually and emotionally compelling. The collaboration between Fincher and Sorkin demonstrated how seemingly mismatched creative sensibilities—Fincher's visual precision and Sorkin's verbal density—could combine to create something greater than the sum of its parts.

The film has also aged in fascinating ways as Facebook's cultural position has evolved. What might have initially seemed like a somewhat harsh portrayal of Zuckerberg now appears almost gentle in light of subsequent controversies involving data privacy, election interference, and content moderation. As one critic noted in a tenth-anniversary reassessment, "The Social Network portrayed Facebook as built on personal betrayal; it couldn't have anticipated that the platform would ultimately facilitate betrayals of democracy itself."

For future generations, the film may serve as a time capsule of the moment when social media still seemed like an unalloyed social good—capturing both the excitement of digital innovation and the first stirrings of concern about the ethics and human consequences of these new forms of connection.

Director Profile: David Fincher

David Fincher established himself as one of American cinema's most distinctive stylists through his work on films including "Seven" (1995), "Fight Club" (1999), and "Zodiac" (2007) before directing "The Social Network." Known for his meticulous approach and technical precision, Fincher began his career directing music videos and commercials before transitioning to feature films.

Fincher's signature visual style—characterized by precise compositions, muted color palettes, and immaculate production design—is evident throughout "The Social Network." His background in commercial and music video production informs his ability to make visually dynamic what could otherwise be static scenes of typing, talking, and business negotiations.

What makes "The Social Network" distinctive in Fincher's filmography is its departure from the darker, more explicitly psychological territory of many of his other works. While films like "Seven," "Fight Club," and "Gone Girl" (2014) explore violence and extreme psychological states, "The Social Network" deals with more subtle forms of aggression and betrayal. The film demonstrates Fincher's versatility and his ability to bring his visual precision to bear on material that is primarily driven by dialogue and character dynamics rather than visceral action.

Fincher's legendary perfectionism—he sometimes requires dozens of takes for seemingly simple scenes—aligns perfectly with the film's portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg as someone with exacting standards and an inability to accept compromise. Actors have described Fincher's directing process as exhaustive but ultimately rewarding, as it strips away actorly mannerisms in favor of more authentic behavior. This approach yields performances of remarkable naturalism despite the heightened nature of Sorkin's dialogue.

"The Social Network" marked the beginning of Fincher's fruitful collaboration with composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, who would go on to score several more of his projects. It also represented a commercial and critical success that solidified his position as one of American cinema's most respected directors, capable of bringing his distinctive vision to mainstream films without compromising his artistic standards.

Behind the Scenes

From Book to Screen

Aaron Sorkin adapted "The Social Network" from Ben Mezrich's book "The Accidental Billionaires," which was still being written during the screenplay development. Sorkin reportedly received chapters from Mezrich as they were completed, creating a unique adaptation process where the source material and screenplay evolved somewhat concurrently. Sorkin conducted his own research and interviews, bringing his distinctive dialogue style to the material.

The film was developed without the cooperation of Facebook or Mark Zuckerberg. This creative independence allowed the filmmakers to craft a narrative that prioritized dramatic truth over literal accuracy. As Sorkin put it, "I'm interested in the bigger picture, the intention of the piece. I wrote this as a painting, not a photograph."

Casting and Performances

Jesse Eisenberg's casting as Mark Zuckerberg proved inspired, with the actor bringing a combination of intellectual intensity and emotional vulnerability to the role. Eisenberg has described approaching the character as "a tragic figure who longed to connect with people but ultimately found it easier to do so through the safety of his computer." Rather than attempting a direct impersonation of Zuckerberg, Eisenberg created a character inspired by but distinct from the real-life figure.

The casting of pop star Justin Timberlake as Sean Parker was initially considered risky, but his performance as the charismatic, paranoid Napster founder earned widespread praise. Timberlake's real-life experience with fame and its pitfalls informed his portrayal of Parker's rock-star persona and underlying insecurities.

One of the film's technical achievements was the portrayal of the Winklevoss twins, both played by Armie Hammer. While some scenes used body double Josh Pence with Hammer's face digitally superimposed, many shots featured sophisticated split-screen techniques that allowed Hammer to interact with himself seamlessly. This technical accomplishment is so subtle that many viewers remain unaware that both twins are primarily played by the same actor.

Music and Sound

The distinctive score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross represented a departure for film music, incorporating electronic elements, distorted instruments, and ambient textures to create a soundscape that felt appropriate for the digital world being portrayed. Their approach often involved creating extended musical pieces from which elements were extracted and modified to fit specific scenes.

The opening piece, "Hand Covers Bruise," with its melancholic piano over electronic drones, sets the film's emotional tone—technically sophisticated but with an underlying sadness. This contrast mirrors the film's portrayal of Zuckerberg himself. Reznor and Ross would go on to score several more Fincher projects, including "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo" (2011) and "Gone Girl" (2014), establishing one of contemporary cinema's most successful director-composer partnerships.

Share Your Thoughts

How do you think "The Social Network" has aged in the years since its release? Has your perception of the film changed as social media has become more embedded in daily life? Do you think the film was fair in its portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg? Share your thoughts in the comments below or join the conversation on our social media channels.